*The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the official views of ICMR.

“You have as many hours in a day as Beyoncé.”

This quote, plastered across social media and repeated in self-help speeches, has become a modern mantra. On the surface, it sounds empowering — a call to make the most of our time. However, while time ticks equally for all, how people experience those 24 hours is far from equal. To claim otherwise is to ignore the systemic disparities that shape people’s lives.

It is tempting to believe that success is simply a matter of time management and personal drive. Hustle culture thrives on this belief, glorifying overwork and treating the absence of rest or personal time as a badge of honour. But, behind the polished narrative of the “rise and grind” mentality lies a flawed assumption; that everyone starts life (or their day) on a level playing field.

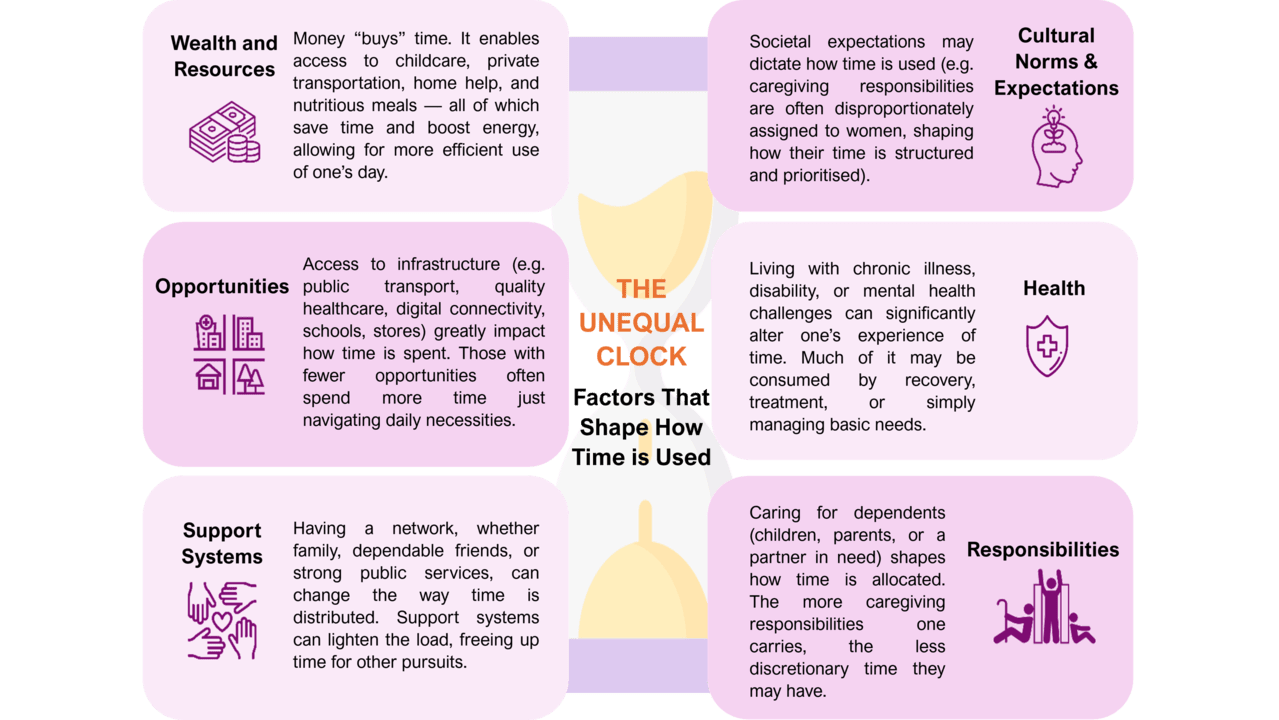

In reality, people live vastly different lives shaped by various social, economic, and structural factors. While we may all technically have the same number of hours, we do not all enjoy the same quality or freedom within those hours. Consider the following factors:

Source: Author’s own

Time is so valuable that in some communities, it is viewed as a currency. Models like time banking allow people to exchange services using time as a medium, recognising the worth of care work and mutual support outside traditional markets.[1]

A 2019 KRI study highlights the extent of time poverty in Malaysia,[2] which is a phenomenon where individuals have little or no time for personal opportunities or rest after completing paid work. The findings showed that many bear the “double burden” of unpaid care responsibilities on top of their paid employment, and this disproportionately affects women (despite working a similar number of hours in paid work as men). This is very concerning as time poverty is associated with reduced wellbeing, poorer physical health, and decreased productivity.[3]

The report reveals a deeper reality. While it is technically true that we all have 24 hours in a day, the way we experience and use that time varies significantly. Consider a single mother working full-time while raising two children. Her hustle is constant, but her path is steep. Or a caregiver juggling Zoom meetings while tending to an ageing parent. Or an individual with disabilities dealing with a challenging environment with no adequate support. These people are definitely not short on ambition or grit. They are navigating uphill battles within systems that may overlook their invisible labour, lack of resources, and reduced autonomy.

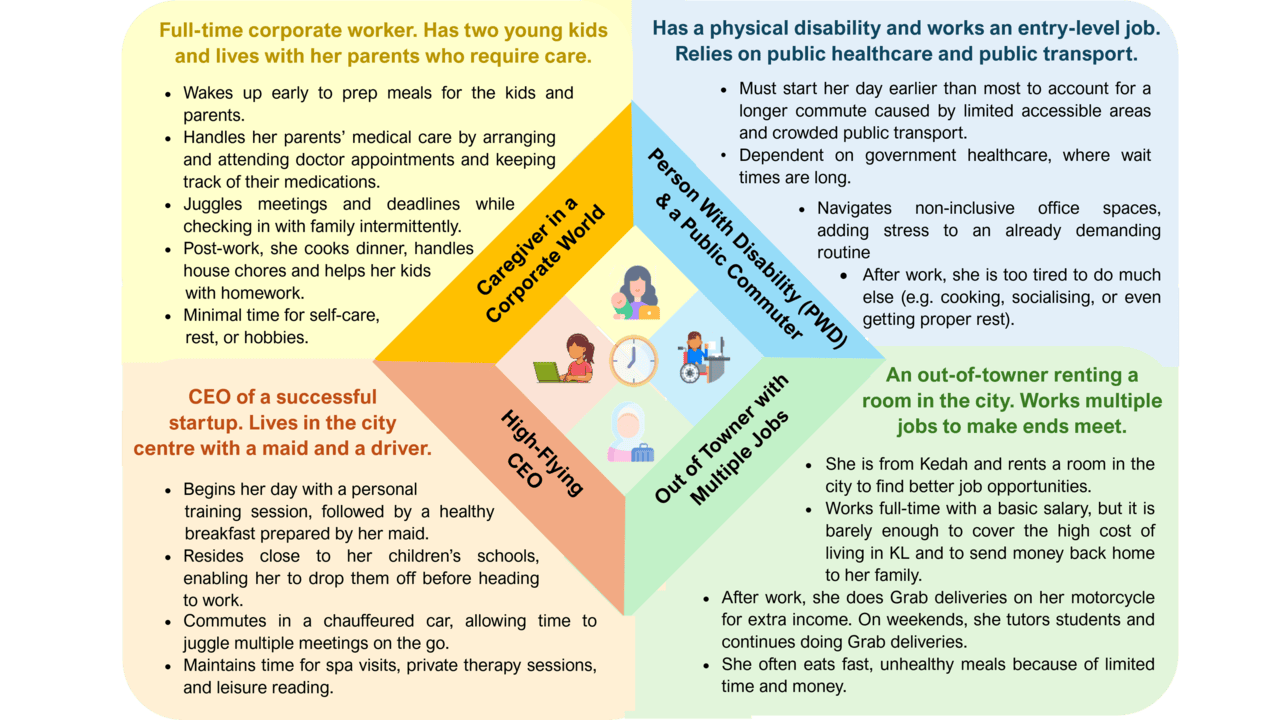

A visual diagram could help illustrate this reality. Imagine four personas, all working women of the same age, whose “24 hours” unfold in different ways.

Note: These personas are intended to be all women, aged 35 and living in Klang Valley

Source: Author’s own

These women share demographic similarities, but the systems they live within (whether economic, social, or geographic) shape how their time is spent, valued, and replenished. Though they may have the same number of hours, the content of those hours and what they cost is very different. Saying they “have the same 24 hours” overlooks important nuances, dismisses real struggles, and may unfairly equate opportunity with effort.

Social media is seen to fuel hustle culture with curated “day-in-my-life” videos showcasing colour-coded planners, 5 a.m. workouts, and marathons of meetings. However, what these videos often do not show are the support systems behind the scenes; domestic help, the cushion of generational wealth, or the privilege of good health rooted in a stable, well-resourced upbringing. This filtered version of success distorts reality. The hustle narrative may overlook the reality that for many, hustling is not a choice but a necessity for survival.

Let’s be clear: this is not an argument against hard work. Resilience, dedication, and determination have enabled countless individuals to rise above difficult circumstances. But hustle culture must not be used as a smokescreen for inequality. When we celebrate hustle without acknowledging disparity, we mask deeper problems and place unfair expectations on those who are already overburdened.

From awareness to action – what role can we play?

With a deeper understanding of the many factors that shape how each person spends their “24 hours”, it is worth asking; what can we do with this understanding? How can we shift from simply noticing these differences to making a meaningful change?

Creating a more equitable future takes effort from both individuals and institutions. For those with more flexibility, resources, or influence, there is a unique opportunity to reduce barriers and expand access so that everyone has a chance to thrive. Employers and policymakers, in particular, have the tools to reshape environments and create empowering conditions that ease everyday pressures and support more people in reaching their full potential.

Certain everyday structures can significantly ease routine pressures, such as:

- Affordable and accessible childcare and eldercare options that help people balance caregiving with paid work;

- Reliable public transport and infrastructure that reduce long commutes and support quality of life;

- Accessible, affordable and efficient healthcare services that does not consume hours in queues for appointments and medications;

- Flexible work arrangements for both men and women in efforts to recognise unpaid care work and improve work-life balance;

- Inclusive education and job opportunities that open doors for marginalised communities; and

- Supportive environments for Persons With Disabilities (PWDs), with accessible transportation and public facilities, adequate medical care, and assistive tools that enable fuller participation in daily life and work.

These supports are not luxuries but are fundamental rights. When we make it easier for more people to manage their time and energy, we are helping them show up more fully at work, at home and in their communities. Moreover, investing in people through such measures is not just compassionate, but a sound economic strategy. Societies that prioritise human wellbeing benefit from higher productivity, improved public health, and stronger generational outcomes.

True equity means recognising the value of all labour (whether paid or unpaid) and ensuring meaningful support for those facing greater challenges. While many are hustling, but their starting points and challenges can be very different. Time should not just be something we race against — it should be something we can make the most of.

References

- Giurge, Whillans, West. (August, 2020). Why time poverty matters for individuals, organisations and nations. Retrieved from GAP – Global Action for Policy Initiative: https://cssh.northeastern.edu/gap/wp-content/uploads/sites/62/2024/07/wp22.pdf

- Khazanah Research Institute. (2019). Time to Care: Gender Inequality, Unpaid Care Work and Time Use Survey. Retrieved from KRI: https://www.krinstitute.org/assets/contentMS/img/template/editor/ Publications_Time%20to%20Care_Full%20report.pdf

- Timebanking UK. (n.d.). How timebanking works. Retrieved from Timebanking UK: https://timebanking.org/howitworks/